Posts

Removing Bottlenecks by Creating a User Interface for High Tech Processes

Introducing automation into your publishing processes can be a powerful way to reduce costs and increase speed, but when those automation tools can only be used by technical staff, you lose some of those efficiency benefits. When I worked with a publisher last year to automate some expensive processes, we controlled costs by creating the scripts first and launching those scripts with the publisher’s technical team to work out any kinks before expanding to their full staff. Now it was time to build a user interface (UI) and expand the automation tools rollout to the rest of the publisher’s team.

My task was to work with the publisher to determine how the UI should work, how it should interact with the existing automation scripts, and then build the app!

Step 1: Identify the Functionality

The first step was to meet with the publishing staff and identify the critical functionalities needed in the app. Fortunately, since I’d also built the backend automation, I already had a pretty good sense of what the app would need to do, but it’s always a good idea to talk with the target users to check your own biases and blind spots. We determined the UI had to:

-

Allow users to upload one or many files

-

Detect whether this is the first time this book has been converted, or is a repeat conversion

-

Trigger the automation scripts (running on AWS Lambda) to convert all uploaded files

-

Show conversion status (in progress, success, failure)

-

Show information about past conversions for any book

-

Allow users with company email addresses to sign-up at will

-

Set user roles (admin or regular user), and allow admins to see all existing files and delete them at will

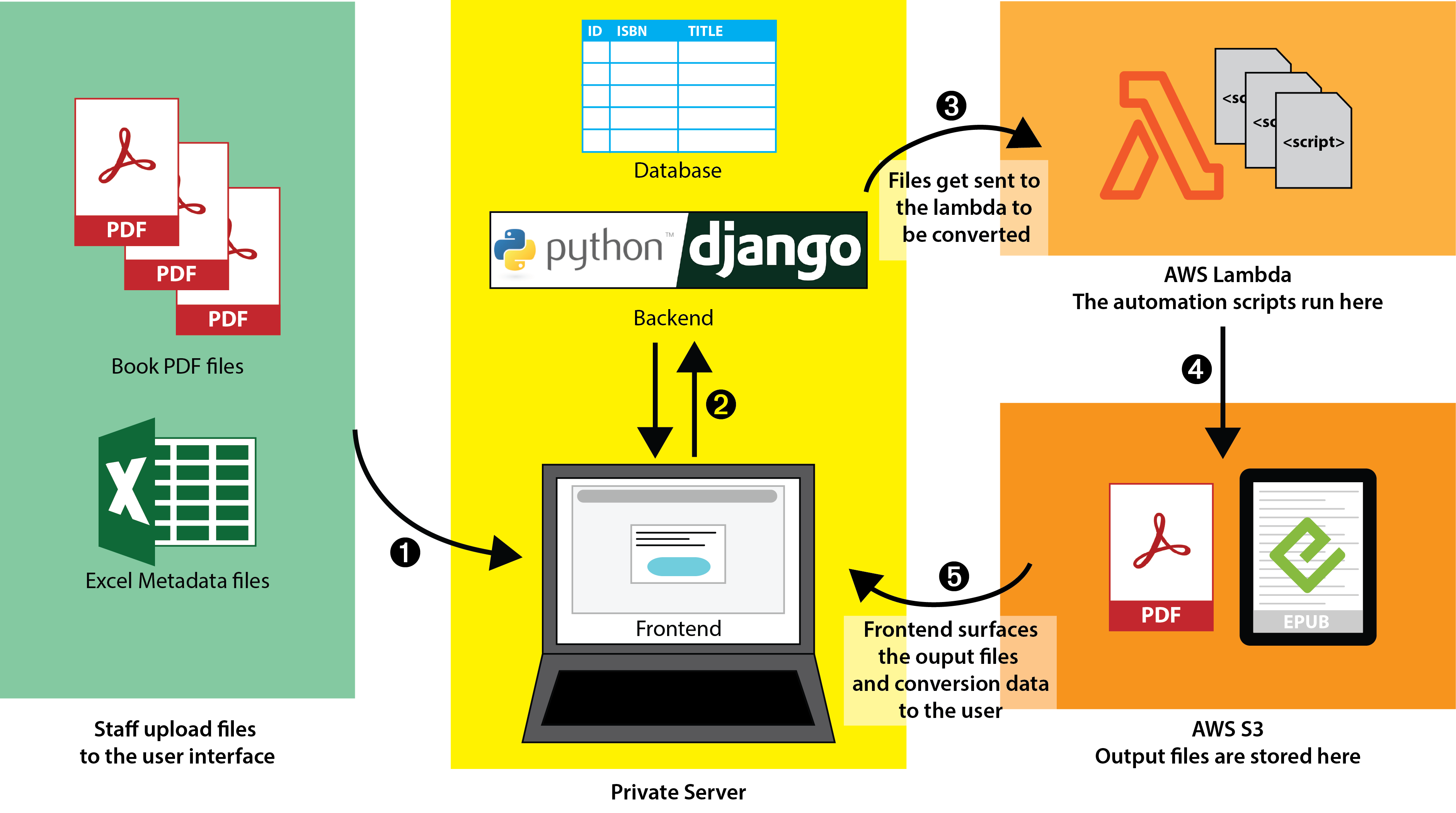

To ensure cost efficiency, we’d leverage the existing AWS Lambda-based automation scripts, connecting them to the new UI without redevelopment. This approach retained the value of prior investments in technology while expanding accessibility.

Technical Architecture

The app would consist of the following new pieces:

Frontend: This is everything we think of as the actual user interface: all the buttons, forms, menus, etc., as well as the functions to connect the frontend to the backend and database.

Backend: Because the app connects to external services (like AWS Lambda and their file storage service), we want to make sure that those connections are kept secure. While it is possible to connect via the frontend only, it is more secure to handle those connections via a non-user-facing backend.

Database: While the ultimate goal is to integrate with the publisher’s title management system, the current approach uses a temporary database. By adhering to the publisher’s existing naming conventions for tables and columns, future data migration will be simplified.

Step 2: Designing the User Interface

To save costs and streamline development, we agreed to use a design framework rather than create custom designs for the UI. This framework provided pre-designed UI components that were generic but functional, perfectly suited for this internal tool.

Next I created rough mockups to illustrate key functionalities, including:

-

Uploading one or multiple files

-

Re-converting books that had been processed before

-

Viewing a book’s conversion history

-

Admin-specific functionalities, such as deleting books, managing server files, and accessing the database directly

I collaborated with internal staff and decision makers for a few rounds of review and feedback via PDF commenting, a familiar process for their review workflows. My primary questions for them were whether the UI seemed clear and easy to use, and whether there seemed to be an obvious path through the app. Reviewing at the mockup stage — before starting development — ensured that the design met user needs while staying within budget.

Step 3: Development Plan

Once we had the functionality and requirements finalized, I met with the company’s fractional CTO to discuss the specifics of their existing server structures and develop a deployment plan. The CTO and I were both fans of using open-source, well-established technologies, which creates a "tech stack" (the specific combination of coding languages and tools used to build an app) that is easier to learn and maintain by people other than myself. We chose to use React (a popular Javascript framework) for the frontend, and Python/Django (a very stable app framework) for the backend.

Originally I had planned to use AWS to host the final app and database; however, after meeting with the CTO I learned that they had an existing server that they were using for other websites owned by the company, and that this server had a robust system in place for backing up data. Since the codebase and new database would be relatively small and therefore wouldn’t require a huge amount of resources, it made sense to use their existing server for hosting; this would reduce the publisher’s internal workflow and knowledge-base requirements by continuing their policy of centralized resource management.

Additionally, while I had originally planned to use a PostgreSQL database, I learned that they were already using MySQL (a similar type of database) for some of their existing websites, that they already had MySQL database management plugins installed on their server, and that their management staff was already trained on how to use these plugins. It was therefore a no-brainer to use MySQL in this new app as well, and the versatility of the chosen tech stack made it easy to pivot to this new database setup.

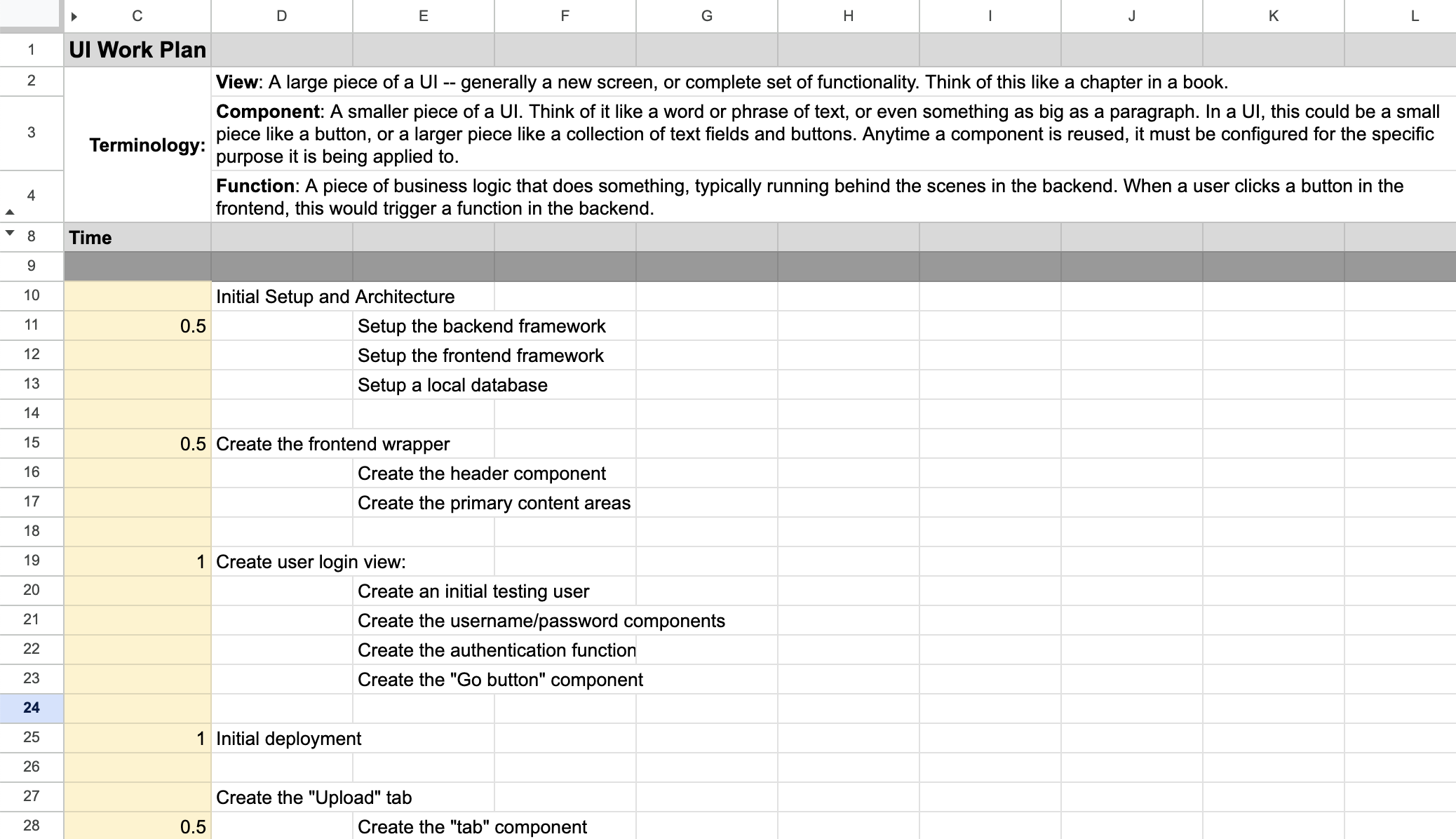

Now that I had a clear plan for the tech stack and deployment, I used the mockups to put together a development plan. I went through and made a spreadsheet of each feature, broken down into individual components, identified components that could be reused in multiple features, and estimated the amount of time required to develop each feature. I then used those time estimates to split the work into 2-week sprints. This gave me a clear plan of attack, and gave the client clear expectations for what completion would look like at any stage.

Step 4: Development, Deployment, and Testing

After all of that planning, development was the easy part! Using the development plan as a guide, I wrote the code, ran it locally to test, and deployed at regular intervals for the client to test as well. Of course there were hiccups — for example, some of the technologies on their server were using different versions than I was accustomed to, which meant they required different methods of configuration; but once again, because we were using well-established and supported technologies, it was easy to troubleshoot and find the solution.

I established a testing plan with the publisher’s technical staff and helped them choose a date to start testing (after all the core functionality had been completed and deployed), so that they could make sure the functionality meets their needs and see if they can catch any bugs or holes that I might have missed. They reported bugs either via Github issues (where the codebase was managed) or via email which I then turned into Github issues, so that I could manage development status in one place, and give the client a clear view into the project status.

Step 5: Hand-off!

I delivered a fully functional app that could be used by anyone in their company, distributing the production workload and speeding up their file conversion time. I included setup instructions to run the app locally (for future developers) as well as deployment notes, should they need to redeploy the app from scratch without my help. While I look forward to working with this publisher in the long-term, I wanted to set them up to be as self-sufficient as possible, so that they’d have complete ownership of the technology I’d created for them.