Posts

Empowering a 1-person publishing team with an automated production toolchain

A fairly well-established tech company approached me to help them build a workflow for their book publishing department, where they publish content related to their products and the larger tech ecosystem within which they belong. Their book division was undergoing a re-launch, and the initial plan was that it would be run by a single employee with the occasional help of other editors depending on the book topic. The challenge was to create a production workflow that could be run by one person and could scale as needed if their book business grew.

In many situations like this, I would set the publisher up with a (mostly) out-of-the-box publishing platform like the Hederis app or Ketty, depending on their internal requirements, and then help them integrate any customizations they might need. However, there were a variety of reasons that an out-of-the-box solution wouldn’t work for this company, and so we settled on building a headless automated toolchain from scratch that included all of their custom requirements.

-

Headless: This means there is no frontend, or user interface, for the application. This is a “bundle of scripts” that can perform functionality but has no visual user interface for non-technical users. (Though some might argue that the Terminal application is a user interface, albeit a simple one, and in fact, we did end up building a very basic frontend, as I’ll describe later.)

-

Automated: The scripts perform the entire layout process without manual intervention. The user sends an input file to the scripts, and they deliver the required output files (PDF and EPUB, in this case).

-

Toolchain: A sequence of processes or tools that, when chained together, create a complete workflow.

As with every automated book production project, I started out with a few questions, the key ones as follows:

What output files do you need?

Generally the answer to this question is a PDF (for print or online distribution) and an EPUB file, sometimes an HTML file (perhaps with accompanying CSS), and occasionally a publisher will have niche requirements, like an IDML file (InDesign’s markup language), IMS Common Cartridge, etc.

This publisher just needed the simplest output: PDF and EPUB, although the toolchain also gave them HTML files as a natural result of the transformation process, which ended up coming in quite handy during the development of the book design.

Will you be printing your books? If so, how picky are your designers?

Anyone who’s met a picky designer knows that they make design choices very carefully; if the book will be printed, then we need to make sure that the designer is working in a CMYK color space for the PDF design, and that the toolchain can output CMYK colors (not all page layout tools support this!).

It turned out print was an important part of this publisher’s distribution plan, and they wanted to preserve their color branding exactly.

Will you be using templated book designs? If yes, will you ever need the ability to add custom design elements on top of the standard template? (For example, a custom color scheme for a book.)

The answers for this publisher were yes and yes.

Who will be using the tool?

For this company, the primary user would be their publishing employee, with possible occasional use by other editors or staff. Their staff (including their publishing lead) have high technical aptitude and almost all have experience with coding in some form or another.

What does the rest of your publishing process look like, outside of production?

Establishing a holistic picture of the publishing process is crucial for ensuring the tool can integrate with the files, people, endpoints, etc., that will be involved.

This publisher would be working with authors outside the company, and the plan was to translate their books into many different languages (since they sell their tech products almost everywhere in the world), which means they’d be working with external translators as well. They’d also be handling metadata in spreadsheets for the time being, which would need to be incorporated into the EPUB file. They would be using Ingram for distribution.

—

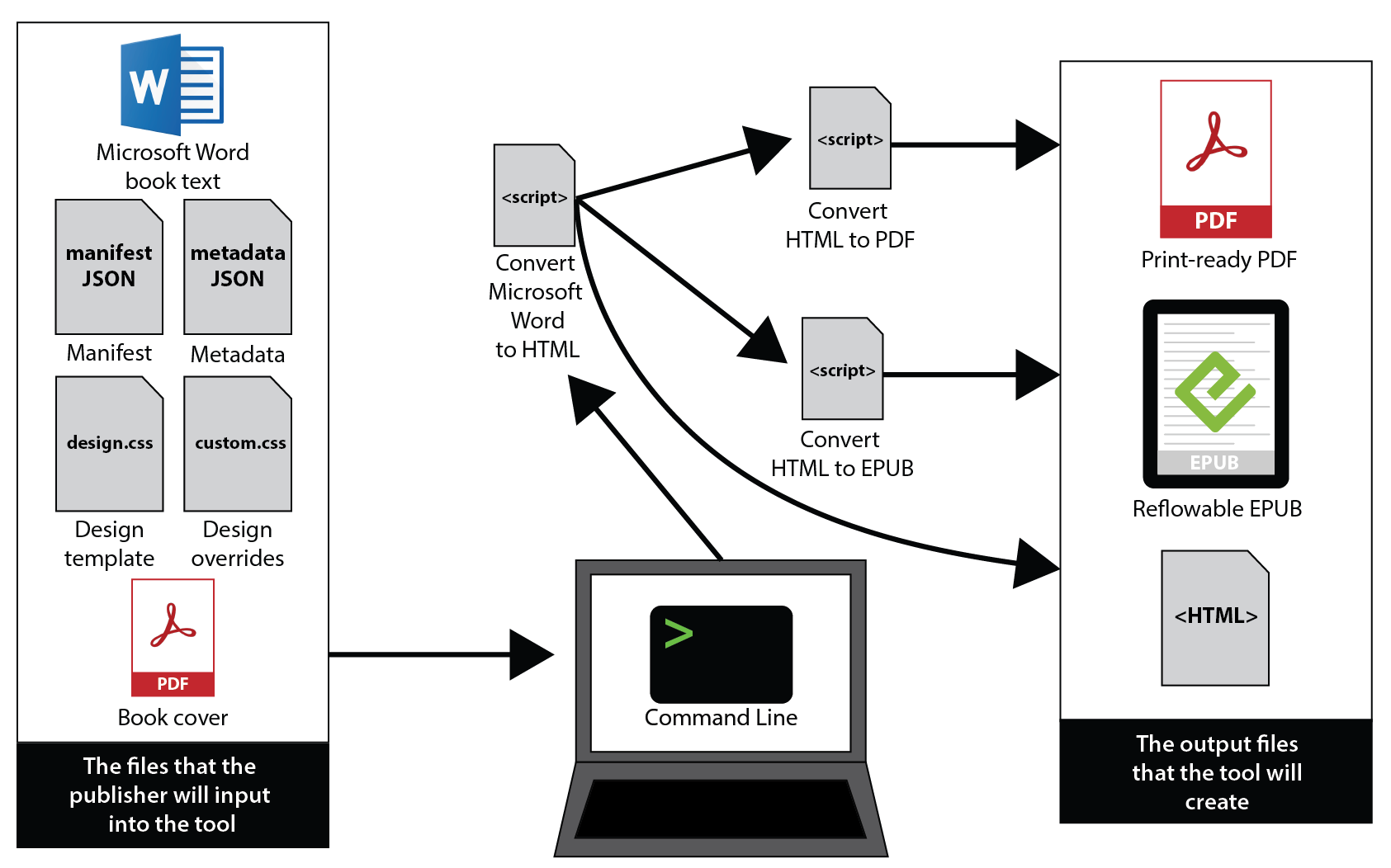

Given these requirements, I developed the following toolchain to support their book production process:

Input files:

-

One or many Microsoft Word files containing the book text

-

If multiple Word files were provided, an additional manifest dictating how to assemble the Word files into a single book

-

A path to any images used in the book

-

A metadata file for the book, containing at a minimum the book title, author name(s), and ISBN

-

A path to a CSS design template

-

An optional cover file for the EPUB

-

An optional design override file (CSS) for this specific book

Optional instructions:

-

Output only the PDF

-

Output only the EPUB

-

Output only the HTML

(There were more options than this, but they were very specific to the way this company would be using the tool)

Process:

-

Convert Word to HTML

-

Convert HTML to PDF

-

Convert HTML to EPUB

Output files:

-

PDF, EPUB and HTML

Because I was working with highly technical staff, it made sense to have them run the toolchain directly on the command line (and in fact, this was their preferred method). I provided script installation instructions as well as detailed documentation regarding what commands to input into the Terminal and how to use the custom options. The user would input one of these commands, press enter, and then the scripts would run and place the final output files in a designated folder on their computer.

Choosing Microsoft Word as the input format was actually a bit of a shift for this company, even though it’s the standard authoring tool for most publishing companies. The company already had established workflows in their documentation department built around using markup languages directly as their input*, so you might think that sticking with those markup formats would make sense (I even helped to build those documentation toolchains, so I was very familiar with how they worked). But given the fact that the editing and translation processes were going to follow fairly traditional paths, it made sense to choose a format that vendors and authors would be able to use without needing additional tech training. There were hiccups, of course, but all solvable. For example: Tech people are notoriously picky about their computer systems (myself included :) ); as such, a couple of editors insisted on using only open-source software, which meant using OpenOffice instead of Microsoft Word. OpenOffice can create files that are interchangeable with Microsoft Word, but it makes some slight alterations in the background XML markup that we needed to account for in the conversion scripts. Fortunately, because I used a modular approach, it was easy to insert this additional conversion step to catch OpenOffice file differences.

*This means that people within the company were writing content using a kind of markup similar to writing code

Another important aspect of building a toolchain like this for a company that is still figuring out what exactly they need is to make sure self-contained parts of the functionality can be replaced relatively easily as needed. I built the toolchain in such a way that the Microsoft Word-to-HTML transformation is self-contained; this means that it could be swapped out in the future if they ever decide that Microsoft Word no longer meets their needs.

For the CSS design templates, I worked with the designer to develop design specs that would work well with automated CSS layout. CSS has become the standard tool for building automated book designs; it’s the same design coding language that is used on the Web, and thus is well-supported and well-understood. The designer delivered InDesign files to me, and I translated those specs into print-friendly CSS, pinging them as needed for clarification or if something wasn’t translating well. I also helped them adjust the design for the EPUB output, for example choosing RGB or hex colors that will look good on a variety of screens even when converted to grayscale (e.g., on a black-and-white eInk device), making sure to use relative units of measurement that would enable readers to adjust font sizes on their eReader devices (one of the most useful features of ebooks, in my opinion), and so on. I also built an option into the toolchain to handle design overrides so that the person converting the book could upload custom design instructions on a book-by-book basis as needed. This came in handy for their second book, where they decided they wanted to use a custom color scheme just for that book.

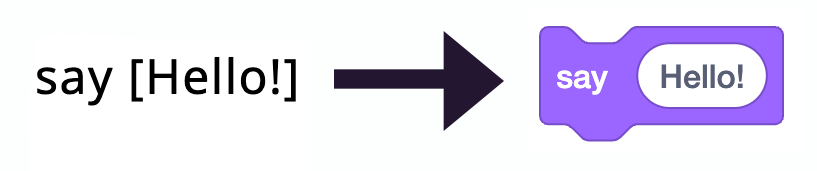

One of the most fun (and at the same time frustrating!) challenges in this toolchain had to do with handling some of the code samples they used frequently in their books. This publisher often referenced a visual coding language called Scratch throughout their book text; this Scratch coding language has its own tools to allow you to write commands as plain-text code samples and then covert those to the visual blocks that someone would use in the Scratch interface. Instead of manually creating images for all of these visual Scratch blocks (which would require updating those images any time they needed to change one of the code samples in the book, which happened frequently), I created a step in the toolchain to detect any code samples written in plain-text Scratch syntax, automatically generate SVG and PNG images of the corresponding visual Scratch block, and swap those images into the converted PDF and EPUB output.

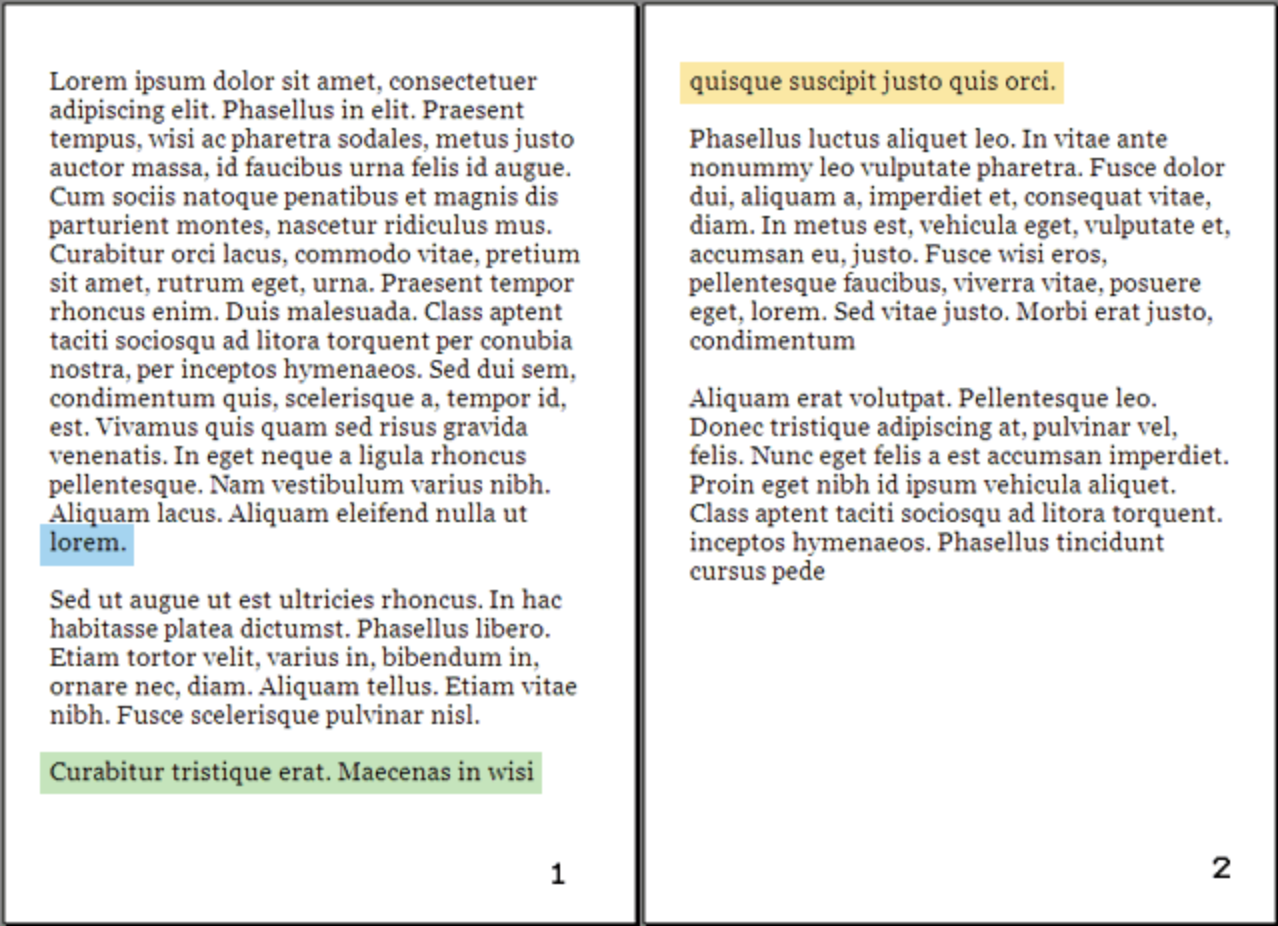

The toolchain did everything it needed to do, creating a print-ready PDF and an accessible EPUB file in a matter of minutes, and I was pleased to see that even some of the other editors were using it to preview the final output of the books they were working on. However, the main publishing staff member did struggle somewhat with the typically-most-annoying part of using a fully automated toolchain: the pagebreaking process (one of the primary reasons I recommend using a tool like the Hederis app instead of a headless toolchain).

“Pagebreaking,” for those who don’t have a background in book production, is the process of going through each page of a PDF and making sure that every line looks good (e.g., that you don’t have three lines in a row that all end in hyphens, or you don’t have too much white space in a line, etc.), and every page starts and ends in a visually-pleasing place (e.g., you don’t have a single line of a paragraph widowed at the top of the page or orphaned at the bottom, you have at least three lines of text on the last page of a chapter, etc.). This is work that goes into almost every professionally-produced book you read, and is designed to make the reading experience invisible — the last thing you want is to be distracted by how the words look on the page. This is also a tediously cyclical process within headless automated toolchains, requiring you to re-convert your files after every change to see how it affects the output PDF.

Even though this is a known issue (and something we discussed going into the project), I couldn’t bear to see the publishing staff member struggle, so as my final contribution to the toolchain, I whipped up a simple visual interface that placed an editable version of the book text on one side of the screen, and the output PDF on the other side, so that the publisher could more quickly and easily preview each change they made. This sped up their work substantially and allowed me to hand the codebase over to their tech team with a clear conscience.

This project developed more organically than some other projects I’ve worked on lately — I had some advance time to build the foundations of the toolchain and program the design, but because the publisher didn’t have a clear sense of what exactly they’d need in their books, a large chunk of the work was done simultaneous with the production of their first book. This required a close working relationship with the publishing staff member and their design team. We centered the work around a Github repo containing the toolchain code — Github is an industry-standard tool for managing coding projects, which comes with built-in tools where the publishing staff member could submit tickets for bugs or new features and track their status.

Overall this was a fun opportunity to build a book production toolchain from scratch for an essentially brand new publisher, and I’m looking forward to applying what I learned to my next custom project!